Making the transition

The move into long-term residential care is a big step and may be difficult, stressful and emotional for all concerned.

Some people with dementia and those who care for them feel a tremendous sense of loss and separation after such a move and some feel relief or mix of both.

The transition for a person with dementia

While everyone is different, even if a person with dementia can’t express feelings and wishes verbally, they may still be upset about leaving home.

They may also feel confusion, sadness and fear at the sense of loss of independence and increased reliance on others. Other common emotions are grief, nervousness over unfamiliarity, anticipation, anger, relief, resignation or feelings of powerlessness.

These emotions may be expressed by changed behaviours such as increased agitation, pacing, trying to leave the facility, aggression, withdrawal, tearfulness or clinging.

It may take time for them to adjust to living in residential care. However, it’s not always difficult and some people settle in quite quickly.

The transition for family carers

Some carers feel there’s a gap in their own life after a person they have cared for has moved into long-term residential care. They may feel a wide range of emotions at this time, including:

Worry: Wondering if they’ve done the right thing and if the person with dementia will be well looked after. It’s important to remember that the decision was made based on balancing what’s best for everyone involved.

Guilt: Many feel guilt, perhaps because they feel they ought to still be doing the caring tasks, or as though they have betrayed the person.

Grief: Caring for a person at home helps retain a sense of the way things used to be, and the physical parting may add another dimension to the grieving process.

Having someone go into residential care can also have positive effects for the people who have been doing the caring, including the following:

- Their lives need no longer be centred around the practical tasks of caring or organising help, so they feel less stress.

- They may feel they have freedom to do things for themselves, when they want to do them

- They may be more able to sleep.

- They may find the lightening of their responsibilities a relief, especially if they or the person with dementia has been physically unwell.

These positive effects may also cause you to feel guilty about having this sense of ‘relief’ – but again it is normal to feel this and this may be balanced as the time you now spend with the person with dementia may be more relaxed and enjoyable – because someone else is doing the physical day-to-day caring.

Help and support

People who have been caring, or family members of someone with dementia who’s gone into long-term care, may find it helpful to talk to others who understand their situation and feelings. They could be friends or relatives, or they might be people like them in a support group, or they could be staff at their local organisation.

Many residential care facilities run relatives’ groups because they understand the difficulties experienced by many relatives once the move has occurred.

Some organisations offer short courses for families and carers about transitioning from home to residential care. You can get information and support at any time from your local organisation.

You could also contact Carers NZ for online support and to find out what support might be available in your area.

Care partners – your new role

As someone who’s been carrying out a caring role, preparing yourself for the period after settling someone with dementia into residential care is just as important as preparing them for the move.

You will likely be dealing with a variety of mixed feelings, and certainly your daily activities will suddenly change.

But none of this means you no longer have a caring role because someone else is doing all or most of the physical tasks of caring. In fact, you’re essential because you are the ‘expert’ when it comes to caring for that person with dementia.

Your role alongside professional care workers is to inform, advise, recommend, help make decisions and encourage the best possible quality of care for their new resident. You can also continue to help out with caring tasks if you want to – how much you do is entirely up to you.

How you can continue to care

The caring partnership you can create alongside the residential care facility should see the person with dementia getting the best possible care.

The advantages of a caring partnership include the following:

- Care is individualised so it meets the needs of the resident, their family/whānau and friends.

- Staff, residents, families and friends work together to meet these needs.

- There’s good communication and an understanding of the resident’s life history as well as who they are now.

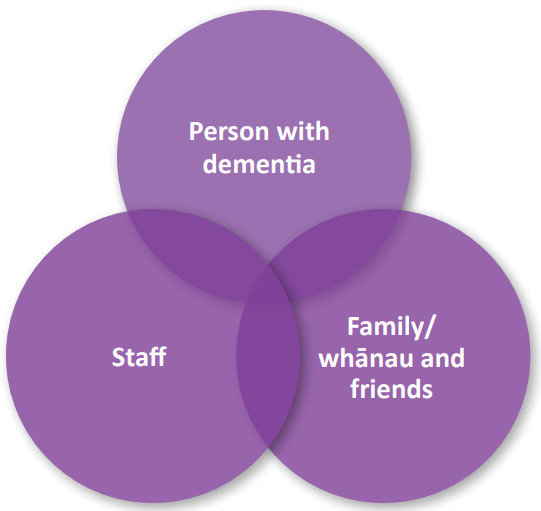

Think about this partnership as three circles overlapping:

On the other hand, you may feel completely exhausted after the move and want to take time out from the caring role. That’s absolutely fine, too.

However, the door should always be open for you to get involved in whatever way you wish. This may be anything from sharing a meal together, helping with showering, to receiving regular information from the facility.

How the facility should involve you

The facility should always welcome and encourage your involvement, and should involve you in caring in the following ways:

- Asking you for information about the family background, past employment, activities and hobbies, likes, dislikes, language, religion and culture of the person with dementia

- Encouraging you to make their room as home-like as possible. This could involve displaying family photos or bringing in objects such as ornaments or religious figures that may have sentimental value.

- Liaising with you to develop a care plan that sets out the person’s needs, goals, strategies and actions to ensure their needs are met.

- Reviewing their care plan with you regularly.

- Regularly informing you about general care issues.

- Consulting you regarding the management of the person’s confusion, changes in mood or restlessness.

- Inviting you to help out with activities, including outings or events at the facility.

- Consulting you about daily living issues, such as the time the resident likes to get up and go to bed, bathing times, what to wear, what to eat, when they like to have meals and so on.

- Encouraging you to read the resident’s day-to-day notes or communication book.

- Acknowledging your arrival and departure with a warm greeting or farewell.

- Inviting you to attend residents/family meetings where the day-to-day running of the facility is discussed, and encouraging your feedback on things such as meal times, menus, activities, communication and accreditation.

Speak up: If the facility doesn’t actively promote the involvement of families and friends you can speak to the manager about how you wish to be involved and the ways they can help you to do this.

Remember your rights: Should you feel the facility isn’t involving you, you may need to get information and support from Health and Disability Advocacy. Click here to find out more or freephone 0800 11 22 33.

How to get the care you want

Here are some tips to ensure you get the care you want for the person with dementia.

- Communicate the person’s needs clearly, for example: “My husband doesn’t like to eat at midday. We need to arrange a later meal time.” “I want to be told of any changes in his behaviour, no matter how small.”

- Give important information to the facility, for example: “My father doesn’t like to talk much.” “Mum likes a shower early in the morning.”

- Explain what is most important to you about the care provided, for example: “My wife has always prided herself on her appearance and it is important that she is well groomed when visitors arrive.”